Synesthesia Boot Camp III - Times Square and the American Musical

The Evolving Sensorium from Vaudeville to West Side Story

Societies and cultures are molded by music, dance and wit. Let’s experiment by identifying societal leitmotifs that we can transform into our own, musical forms that helped shape society, drive human experience and expand our acquired synesthesia. I will apply this particular exploration to the development of American Musical Theater in and around Times Square, New York’s Theater District. Think of this dense district of urban exchange as a blueprint of the mind, evolving from raw, rough, emerging forms into musical illumination.

THE NASCENT STAGE

Vaudeville

It starts with vaudeville, a variety-oriented mix of music and comedy, the main form of mass entertainment as the 19th Century turns into the 20th. It’s the most democratic art form in American history, evolved from raw, rough edges. You dance, laugh, boo and throw debris at seemingly intentionally bad acts, often while imbibing alcohol. Times Square becomes the nexus of vaudeville, the center from which shows are conceived, showcased and circuited across the nation.

Dance

Dancing becomes an institution of its own as the ragtime music of the day and the easing of sexual inhibitions would create audiences viewing provocative dance numbers and then participating in provocative dancing of their own. The beat of dancing feet, whether propelling a professional hoofer or a haggard pedestrian, has become core to the fiber of the district.

Algonquin Roundtable

Simultaneously, the written word rises to great heights on Broadway as pedestrian mass proliferates. The New York Times builds a new headquarters (One Times Square and hereafter referred to as the Times Tower) at the same time that the new massive subway station is being dug in the sub-terrain. Not long after, a block away across 6th Avenue in the Algonquin Hotel, a group of acerbic authors and critics create a roundtable to carve up the latest cultural offerings in cunning metaphors. Dorothy Parker states: The first thing I do in the morning is brush my teeth and sharpen my tongue.” The Gutenberg revolution that began 500 years earlier shifts into hyper-speed, prickling with attitude.

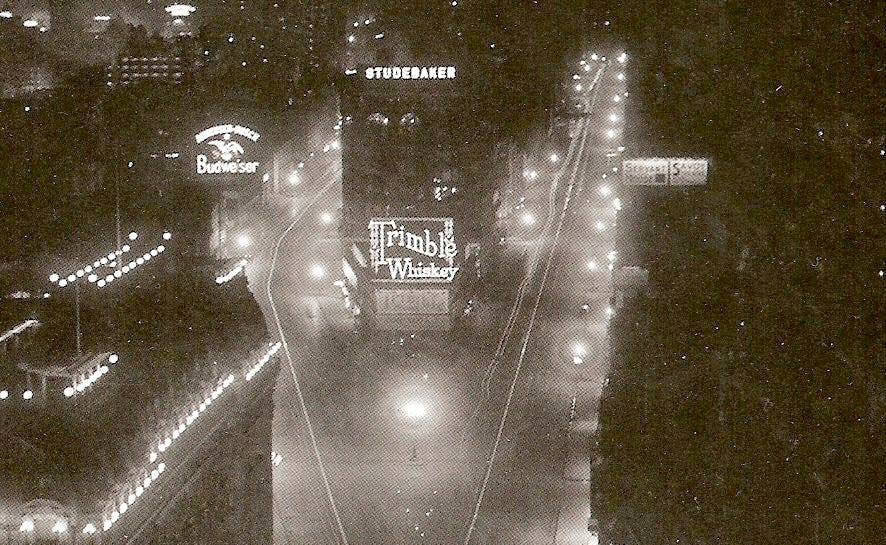

Electric light and its usages, from utility to entertainment, evolves rapidly. At the turn of the century, the mere presence of bright light after dark was surely a miracle to the inhabitants of crowded cities. But soon in Times Square, light becomes larger than life. A stage for showing vaudeville or plays is confined by the size of the theater, but light can travel across city blocks and up the sides of buildings. The openness of the square, set by the split of the avenues, acts like a window and escape valve into and out of the human psyche. It creates ideal sight ratios, perfect for beaming messages to the pedestrian masses. Why not make light dance, forcing deep psychic impulses to rise to the surface? With the deep pockets of consumer products companies pumping the exchange, we see huge flashing displays integrating the effects of the live shows playing in the theaters below.

And as light technology ascends, so does the new art form of cinema. In its nascent stage, cinema is shown on small machines in nickelodeon parlors or takes the form of one brief act in a vaudeville show. Vaudeville swallows cinema at first, but rapidly cinema devours vaudeville.

And thereby vaudeville transforms under this pressure into a more engaging offering of elegant staging, costumes, and more polished talent, The Ziegfield Follies and other revues. This is a magic ratio of music, comedy, dance and beauty.

Shuffle Along Medley

The musical Shuffle Along by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle rises on Broadway, bringing syncopation and jazz rhythm to the stage. A new age of dancing and musical reverie rises across America.

THE ACCELERATION OF CONVERGENCE

New developments would dramatically alter the ratio of the senses. Radio’s emergence, plus advances in broadcasted, recorded and amplified sound bring news events instantly to the masses. Music and aural entertainment are freed from the confines of natural space, just like light traveling across buildings and blocks. Now the composer, the former Tin Pan Alley operative, is elevated as the driving creative force. George Gershwin, Eubie Blake, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, Irving Berlin and the team of Rodgers and Hart mix ragtime, jazz, classical, and dance, aided by the proliferation of recorded music. Jerome Kern trail-blazes the concept that the “book” drives the musical revue into a coherent form rather than being subservient to melody and dance.

By the late twenties, the American story-driven musical is born with breakthrough shows like Strike up the Band composed by George Gershwin and Showboat, composed by Jerome Kern and produced by Florenz Ziegfield. The standard formula of melody, spectacle, beauty and dance can no longer stand out in a world dominated by movies and sound. Creative forces must dive deeper into the human spirit.

Ole Man River - Paul Robeson

Listen to Paul Robeson in Showboat sing a song birthed from the Spirituals of the southern slaves, a life affirming anthem of perseverance.

And now another breakthrough in the shifting plates of sense ratios. Just as the musical continues its integration of the senses, movies begin to talk and sing. Cinema now serves both sight and sound, and of course the most endearing form of sound is music. From the very beginning, Broadway is the content of sound cinema. The Jazz Singer starring the vaudevillian Al Jolson and featuring many of his most renowned songs, is the first major sound film.

Busby Berkeley Dreams

The Broadway choreographer Busby Berkeley, a pioneer in the crossover between Broadway and Hollywood, powerfully integrates dance, film and music by staging musical numbers that spill off the stage into an expanded cinema space, much like how the lighting spectaculars had climbed up buildings and across city blocks.

GOLDEN AGE

Into the next decade, the institutions of Times Square eschew linear evolution for exponential. The electric light display transforms under Douglas Leigh, its next great innovator inspired by the World’s Fair of 1939 in Flushing, New York. Leigh views the city and the mind as a canvas upon which carnival-like promotion can be painted with precision, playing upon its environmental features. According to Darcy Tell in Times Square Spectacular “He carefully considered the visual possibilities of his sites – how high they were, how far and from which direction they could be seen, and how they related to nearby signs.” Influenced by cinema and the short cartoons that often accompanied a movie feature, Leigh and his peers develop technologies that enabled street-size displays incorporating moving neon images, oversized cartoons, and larger-than-life consumer products. Giant coffee cups ooze steam, huge smoke rings emanated from a cowboy’s mouth, and models on top of the Bond Clothiers building are placed alongside waterfalls and flashing lights.

Through the nourishment of these expanding and altering sense ratios, the American Musical Theater blossoms; it’s the era of Rogers and Hammerstein, Bernstein, Loesser and the maturity of Berlin and Porter. There’s no denying the impact of the sensorium around them. Radio has become a standard in every home and swallows live vaudeville. Sound cinema expands to provide a more powerful ratio of the senses with engaging storytelling, cinematography, character development, editing and musical score. And of course these artists are witnesses to the evolution of light spectaculars in Times Square over their decades of work within the district. Not only are these mediums gaining cohesiveness, they’re churning out content at breakneck speed.

With Oklahoma in 1943 and the superior Carousel in 1945, Rodgers and Hammerstein attain a new level of acquired synesthesia that reverberates for thousands of curtain calls. As Meryle Secrest stated in her biography of Richard Rodgers:

“Oklahoma’s uniqueness stemmed from the extent to which song, dance, story, costumes, scenery, and lighting had coalesced into the kind of total theater so often extolled in theory and so difficult to achieve in fact. As Mark Steyn wrote, ‘Rodgers and Hammerstein …fused the naturalism of the straight play, the musicality of the operetta, the color and imagery of musical comedy lyrics and the emotional sweep of dance.”

Yes, the Gestamkunstwerk, the Total Artwork, that elusive ecstasy when the elements of the theater of the mind, perpetually developing at various stages, suddenly burst to the surface in fortuitous integration.

Billy Bigelow's Soliloquy from Carousel

Let’s contemplate this piece, sensing every churn in Billy’s emotional spectrum as the melody transforms; fear, love, pride, anger, and steadfast determination.

And then another blaze of light breaks through the boundary of our capabilities. Bernstein and Sondheim create West Side Story; Shakespeare’s drama, the spirit of Dorothy Parker’s acerbic tongue via Sondheim, and extraordinary dance conveying sexual awakening, satire, and violent emotions. And musical styles, from classical to opera to ballet to Afro-Cuban to clave, merged in ways that few could ever dream of.

America, In all its Colors

It’s the wild, turbulent, dangerous dance of Dionysus anchored by drama and wit.

Tonight Quintet

And no one could be happier than Shakespeare, the impresario who mastered bringing psychological forces to the surface.

So we conclude this part of the journey, musical theater metaphorically speaking for the human psyche, an exploration of cultural transformation via the converging senses and emotions that we can, with drive and creativity, apply to our individual sensibilities.